Why do local English Folk dance

clubs fail to excite people? Why is English Country Dance these days generally viewed as

dismal, slow and unexciting? A discussion - including a contrast to Irish dance.

"...........folk song and

dance, like so many other hobbies and activities, is not immune from feud and

vendetta."

"Dancing is nothing if you

just consider steps, you have to express yourself with the eyes, face, gestures and convey

your passions to the others"

"...................... a

fascinating insight into what was, in essence, a cultural civil war with dance as the

arena of combat."

NOTE: split this page into several pages

sometime. Updated Sept 2022.

Despite not being a 'natural born

dancer' I have become quite proficient. My dance diary for 2016 shows how much fun and

exercise can be had for a few hundred pounds a year.

Highlights of my dance year in 2016 are here - see if they

encourage you to take up the hobby!

Since taking up dancing over 15 years ago I estimate I have danced about 40,000 times and

with hundreds of different women.

Principal links to folk dance material on this website.

Dismal, slow, unexciting and

boring?

The image of English Country Dancing (folk

dance) is simply one of boredom. I have sometimes thought this myself - and if it were not

for attending various dance festivals I might have given up the hobby many times.

The example of Totnes Folk Dance

Club, and others in Devon.

One example from my early years as a dancer

is a useful illustration of the problem. It is centred upon the now defunct Totnes Folk

Dance club in Devon.

In their final ten or more years of existence, Totnes Club was not renowned for

liveliness. One evening I drove alone to a Saturday night dance featuring the Dartmoor

Pixie band. It was probably around 2007. As usual the dance was being held in the Totnes

Civic Centre, an expensive venue with problematic parking in the centre of town. I arrived

at the hall a few minutes late. The dance had not yet started.

I looked around the hall for any likely partners. There was an assortment of glum

looking couples, all over 80 years old (or dressed and behaving as though they were over

80), sitting as still as still could be. The band was playing. No-one was dancing around

the room - not even to the Dartmoor Pixies who are about as 'danceable' as any local band.

Further glances around the room did nothing to change my view that I'd be better off at

home - so for the first time in a folk dancing career spanning over a

decade, I walked out and drove home. The air of boredom, lethargy and overall weariness

was palpable. This - so it seems - is also the typical image of English Folk Dance clubs.

Some years later (and to no-one's surprise in the local folk dance world) Totnes Folk

Dance Club closed down after a few decades in existence. The people running it and all or

most of those attending simply got too old and too satisfied with their own increasingly

slow way of doing things - and they never bothered or wanted to attract any newcomers.

Several other local clubs have gone the same way. My local club at

Sidford may soon follow

- as of 2016 it had about 24/28 regular attendees - down from 60 to 70 ten years earlier.

Post-Covid however it is still going, with about 16 to 20 people attending. In the list of local failures can be listed Budleigh, Honiton, Lucky Seven (in south

Devon) and Totnes. Exmouth Folk Dance Club was set to close at the end of 2016 but

was revived for a further year.

Many clubs seem to fail when numbers attending regularly fall below 20. Certainly it is

difficult to do some types of dances with fewer than 24 to 30 people. Sometimes a club

will dwindle to 8 to 10 members before being wound up - the Lucky Seven was one example.

In general, numbers below 20 indicate the club is on life support. Against that, a few

small Irish Set Dance clubs and American Square clubs survive on 8 to 10 attendees if they

can obtain a modestly priced venue and if they have organisers who are so keenly

interested in promoting dance that their enthusiasm rubs off. In these cases, the only

cost is often the venue - the organisers provide the PA and do the calling for free and

(crucially) the dances are all done is squares of 4 couples so 8 to 10 people is an

adequate number.

In one or two cases organisers expended considerable effort to obtain new recruits, in

others, the club closed simply because no-one wanted to take over from organisers who had

grown weary. This pattern has been repeated across the UK and was a recurrent theme in Set and Turn Single magazine - this ran as a paper edition for 17 years

and with some lively cut and thrust debate especially between 2011 and until July 2016

when the last issue appeared. It was replaced by an 'on-line forum' which, to no-one's

surprise, has failed to generate a fraction of the interest of the paper based magazine.

Social, Fun and Flirting - the key

ingredients?

So why are folk dance clubs in the UK

closing down? One letter in Set and Turn Single issue 74 (from

Tony Weston who says he has been dancing for over 50 years) laid bare the perceived

problems of image. In the next issue a spirited dancer and caller,

Linda Selwood, used three words - social, fun and flirting to say what dance used to be -

and maybe still should be.

It is (I would argue) the latter that is especially missing from so much English Folk

Dance despite that (at Chippenham Festival a decade or so ago) a dance instructor taught

that dance is in essence flirting - a mating display - as in peacocks. One sensual dance

move (if done correctly) is the gypsy (see here for a copy of

the instructions from Cambridge) yet I sometimes get abrasive comments from people about

'being too forward' - yet I get more comments from women along the lines of 'how nice to

have a man who looks at me properly' - this letter from STS82

gives details. Many women (and men) complain that English dancers refuse to engage with

their eyes: instead of looking at their partner they look at the floor.

Quite recently a dance display by a bird of paradise was filmed for the first time for

a BBC nature programme. This

link might work. Earlier, it was reported:

"Darwin thought that dance was a part of the mate selection process and more

recently two groups of researchers (Brown et al., 2005 and Fink et al., 2007) suggest that

the way we dance might be influenced by our hormonal and genetic make up, such that we use

dance to communicate the quality of our genes to potential mates."

For some years, and especially after I became 'well known' via STS

I have experienced hostility to my deliberately outgoing 'style' of dancing - to flirt as

much as is reasonable. Yet it is (arguably) what is so much needed in clubs to revive them

- and they need new and younger members. In essence therefore it is dancers themselves (or

at least some of them) who are imposing a restriction on the 'fun and flirt' aspect of

English Folk dancing.

I know various women who

particularly enjoy dancing with Steve Wozniak because he can usually be relied on to liven

things up. (STS issue 89)

Dr Clio Cresswell (youtube

screenshot) |

Flirtation is a key part of

what keeps people young. It has been the subject of numerous 'social science' studies.

What matters here is simply to admit that it exists and that it is a central part of many

dance types. One of many 'how to flirt' discussions on TEDx is a talk centred on the HOT APE concept - it is in

my view one of the least intelligent of all the TED talks I have ever watched. The

presenter received only restrained and polite applause - in contrast to the standing

ovations given to many TED speakers. Another woman who gave a 'sexual' lecture devoid of

any real content was Mary Roach.

- but do watch it if you wish to see a pig being artificially inseminated.There are dozens

of similar TED talks, most of them by women and ranging from casual sex through to analysis of marriage.Dr Clio

Cresswell, a senior Lecturer in Mathematics at the University of Sydney, gave a more

entertaining discussion of mathematics

and sex - but I doubt her ideas, equations or high heels will ever catch on amongst

folk dancers.

To redress the male/female balance, there are dozens of talks on computer technology,

hacking, and stuxnet, mainly by

men. Those by Pablos Holman I

find particularly entertaining. He might act and dress like a dishevelled hippie - but

he's seriously bright, as are most TED and TEDx speakers. The film Zero Days is also centred on

stuxnet-type risks.

If you think you're good at mental arithmetic, try this. |

At Lichfield dance festival in 2016 veteran

caller Mark Elvins stressed the 'fun and flirt' aspect of Zesty Playford dance - as

opposed to the perceived formality and correctness of conventional Playford. Playford

dances are still well patronised - but it is a genre very much for older people. He didn't

get much response from his Lichfield audience. Closer to home, Jane Thomas and Simon

Maplesden (both callers at local clubs in the West Country) also often try to

inject some light-hearted innuendos into their evenings - Simon sometimes

exhorts dancers to 'feel the goods'.

The dullness and inhibition that some self-appointed arbiters of dance etiquette would

see imposed on all dance clubs and festivals is in stark contrast to what happened in

Ireland (and probably in England) in typically 1910 to 1960.

The 'social' aspect of dance is also important and is

arguably a feature that made Gittisham Folk Dance Club

so successful in its middle years when it was run by Douglas and Margaret Jones

- it was in those days a club where people went to find friendship as well as

dance. In the middle years of Gittisham club

there were home made cakes and other treats every week - all freely given and eagerly

awaited. Other clubs have very little 'social' aspect to them but thrive because they

offer so much 'fun and flirt' - jive clubs often follow this route to success being (so I

am told!) essentially a 'pick-up joint' and not only for younger dancers. This too has a

long history as a part of English Country dance. The potential for song and dance to

combat loneliness is also discussed in detail in my summary of folk festivals in 2016 - simply because the ideas occurred

to me at a festival.

So - does the image of sheer boredom of English Folk Dance come simply from the lack of

willingness to engage in what is a central theme of dance - flirting? It cannot be as

simple as that - yet it is in my view a part of what needs to change. Other forms of dance

such as jive and salsa that are more outwardly flirtatious used to attract hundreds of people.

English folk dance clubs are lucky to attract a single new recruit each year. Contra dance

is more overtly flirtatious: it is faster for a start and swapping partners is encouraged.

There is also a lot of swinging - which can be done with partners quite close together. It

is sometimes hugely popular at dance festivals yet very few local clubs of any size exist in the UK.

Of those that do, some have become infected by 'politically correct' and 'woke'

ideology that includes gender neutral calling. In this, people can dance

whichever role they wish despite their biological sex - and it has become

'impolite' to refer to people as either men and women. Hence they are referred

to as larks and robins, or larks and ravens (people on the left and right of a

couple dancing as partners). This suits trendy and LBGT people but does not make

dance appeal to the vast majority - and some dancers I know avoid Bristol Contra

just for this reason. Gender neutral calling is further discussed below.

|

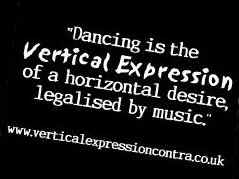

One of the most admired and

energetic of English Contra dance bands - Vertical Expression - sell T-shirts

and bags emblazoned with their slogan "Dancing is the vertical expression of a

horizontal desire, legalised by music". Go back 50 or 100 years in England or

Ireland and they would have been banned, ejected from dance venues and condemned by

self-righteous priests. The expression is variously attributed to George Bernard Shaw and

to a US poet Robert Frost (1874-1963). There is even a music video, and numerous historical

accounts of how dance was equated to sin and the devil.

A related problem - highlighted in several places in my dance

diary - is that once a dance club becomes 'overwhelmingly slow and old' it is then

virtually impossible to attract and keep younger members. Ideally therefore, clubs need to

try and attract new and younger members before they reach this 'terminal decline' phase. |

Ireland and England - chalk and

cheese?

"A way of life is now no

more. Its demise was not gradual and natural. On the contrary, it was brutally and

prematurely ended.

All the more reason to lament its passing."

I do both Irish Set Dance and English

Country Dance passably well. What has always struck me is the far greater emphasis on

dance as a part of Irish identity and culture compared to how English Country Dance is

viewed in contemporary England. It is more vibrant, there is more emphasis on teaching and

'getting it right'.

It is also unashamedly a part of heritage - witness the playing of the Irish anthem at the

end of most Irish dance weekends - and the display of the flags of both Ireland and the

counties of Ireland. There is nothing comparable in England. But why? English Country

Dance - if the slow interpretations of the Playford genre are discounted - and if done

with some enthusiasm, can be every bit as exciting as Irish Set Dance. Yet there are so

few local dance clubs in which you can find good quality fast English folk/ceilidh dance -

and many in which you can find dullness and age-related degeneration, often combined with

incompetence.

I'm not a dance historian but surely there must be a few clues as to how English dance

could be rescued from the doldrums - much as Irish dance in its several guises underwent

revivals in the latter part of the twentieth century, and with interest having been

maintained to the present day.

More often than not, the church (or people of a church persuasion who see themselves as

arbiters or guardians of what is right and wrong) have been at the centre of trying to

tell all other people how to run their lives - including which dances they were permitted

to do, in which styles and even in which buildings.

|

Often their 'moralising' has been presented as a desire to 'protect others' yet so often

seems to have been more of an excuse utilised by 'control freaks' to try and inflict on

others their own narrow minded preconceptions. I give contemporary examples from English

folk dance clubs here and especially from Eastbourne Folk

Dance Festival here.

Quite recently (2022) 'making

people feel uncomfortable' has become the favoured phrase of 'woke' culture

- and in universities (to use a parallel description) 'cancel culture' in

which speakers are denied a platform because their views might offend some

minority view.

This example is from Oxford, another example is Nottingham

where the Chief Constable (as was?) decreed that wolf-whistling at a woman

(typically from a building site!) would be viewed as a 'hate crime'. |

|

The police have

embraced 'woke' culture probably because it is so much easier to deal with

trivial issues than address real crime. No matter that violent crime is

soaring, that burglaries are rarely investigated (and very rarely solved)

and no matter that vehicle crime costing hundreds of millions of pounds is

largely unaddressed - what matters is that people (often women with an

oversized chip on their shoulder) should not be made to feel

'uncomfortable'.

In the area of folk dance, what many self-righteous staid dancers seem unable

to tolerate is watching so many women having a whale of a time with a dancer who

puts far more enthusiasm into dancing than they are capable of doing.

Examples of the 'control freak' mentality from Ireland in the last century

are given below.

|

|

Self-righteous moralising

continues of course in Ireland with their arguably archaic abortion laws - but don't let's

get too far into that argument. A update article on abortion was published in the Guardian

on 24 October 2016. The author, Una Mullally, a (lesbian) columnist for the Irish

Times, argues essentially that the Irish abortion laws (like those recently advocated in

present day (2016) Poland for example) have their origins in "Catholicism, misogyny

and an obsession with control".

Una Mullally is a brave woman, and not only because of her writing on women's issues.

She has also recently described being

diagnosed with stage 3 bowel cancer in 2015 - a type usually seen in men over 60. So

far she has survived.

This photo is from her twitter account.

A later Guardian article outlined the

scale of adoptions forced upon unmarried women by the catholic church even into the

1970s. Access to abortion was also central to a case brought in 2016 in the

Supreme Court on behalf of women in Northern Ireland. More recently of

course (2022), ideological Catholics in the USA have overturned "Rode vs

Wade", thus ensuring that a world that has far too many people already will

have far more, and often born to parents who are less than wholly capable of

looking after them. |

History - and the 'joy of sets' :

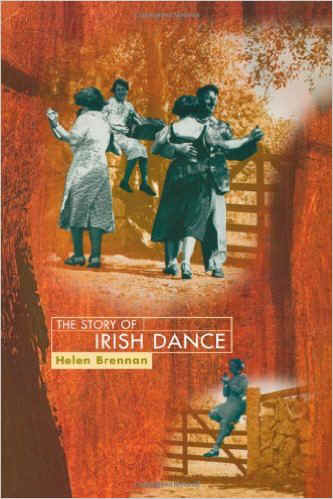

In discussing what can be learnt from Irish

dance I'll start with some extracts from a book on the social history of folk dance in

Ireland published in 1999 - "The Story of Irish Dance" by Helen Brennan (ISBN 0

86322 244 7). The author describes the brutality of life in Ireland in the 1920's and

earlier, the Dance Hall Act of 1935 that did so much damage to traditional Irish dance

(the type and in the places where the people wanted to dance and the priests wanted to

curtail) and finally the explosion of interest when the sexual side of Irish dance was

finally unleashed in 'Riverdance'. It might make you wish to read a copy.....or maybe to

see a similar revival in the fortunes of English Country Dance. These extracts are

followed by some highlights from a recent BBC TV series - Dancing Cheek to Cheek - the

history of dance in England over the last few hundred years.

The following extracts from The Story of Irish Dance are worth reading because they

give such a feeling for the historical context of the revivals. Both these extracts, and

my summary of the BBC TV programmes that follow, highlight that dance has always been

beset by rivalry and disagreements as to what is 'right and proper' - both in dance types

and in utilising dance as an expression of desire.

There are many films on youtube covering the history of Ireland - I'd recommend (part 1) and (part2). Each is nearly two hours

long and best streamed to a large TV. Emigration to America to escape the

poverty of Ireland a century or more ago is also covered in Helen Brennan's book.

|

"THE STORY OF IRISH DANCE

is a serious study which succeeds in being both entertaining and stimulating." -

IRISH NEWS (Belfast)

"THE STORY OF IRISH DANCE is of interest to the general reader and as a source for

scholars of Irish dance, dance anthropology, folklore and cultural studies" - IRISH

TIMES (Dublin)

" .. a remarkable collection of anecdotes and well-researched background... a

fascinating account." - IRISH INDEPENDENT (Dublin)

"THE STORY OF IRISH DANCE is a catalogue of extraordinary anecdotes, meticulous

research and the rehearsal of acrimonious controversies whose effects linger on

today." - THE EXAMINER (Cork)

"Helen Brennan has written a fascinating account." - R.T.É. GUIDE (Dublin)

"THE STORY OF IRISH DANCE really is a story to be read by anyone with an interest in

any form of dance .." - DANCE EXPRESSION (U.K.)

"THE STORY OF IRISH DANCE is a must, not only for Irish dance fans, but also for

anyone interested in Ireland's wonderful past. Helen brings history to life." - IRISH

DANCING MAGAZINE

"This book not only weaves a social tapestry around the dance but is also a reminder

not to lose sight of the basics. It is a 'must' for anyone involved or interested in Irish

dancing." - SET DANCING NEWS (Ireland)

These quotes are taken from a review on Amazon's website. I'm assuming they are genuine. |

|

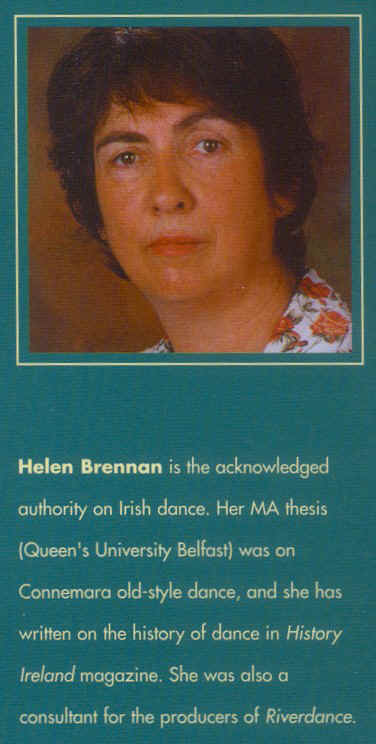

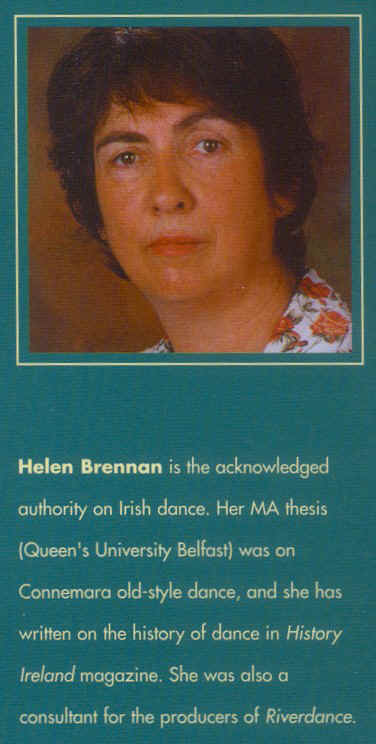

Helen Brennan:

He suggested that I call to see Jimmy Ward, a member of the Klifenora Ceili Band who lived

locally, to see if he could help. Jimmy was happy to oblige and it was thus that I

conducted my first interview on dance. In Jimmy's snug kitchen I listened fascinated as a

whole world unfolded. He talked of a "fund-raising dance" during the 1930s when

the "detectives" - members of the police force based in the area - raided the

house and every man was punched and kicked as the dancers were ejected from the premises.

Jimmy was spared a beating that time as he was a visiting musician from a different part

of Clare. The police action was taken ostensibly on foot of the recently enacted Public

Dance Hall Act (1935).

The act effectively banned dances in the houses of rural Ireland and put pressure on

people to attend only formally organised dances in the newly built halls, most of which

were run by the local clergy, and did not find favour with the people who had previously

organised their own dances on all kinds of occasions. Jimmy went on to talk of happier

events: card playing combined with dancing, "tournaments", "swarees",

and "joined dances", when the jollity sometimes went on all night and the

company returned to their homes as the sun was rising in the sky............

The tensions implicit in any national cultural organisation during a period of major

change began to come to the surface, and it became obvious that the favourable reception

of the Keating Branch to the London Gaels' programme of group or figure dances was not

necessarily shared by the general membership of the Gaelic League. During the early

1900s the great debate as to which dances were acceptable and which were not raged in the

columns and letter pages of An Claidheamh Soluis, the Gaelic League's newspaper, as well

as in other publications of the period. The weapons of political debate - vilification,

ridicule, scorn and caricature - with their attendant power to wound and alienate, were

all employed in the debate which surrounded the attempt to create a canon of Irish dance.

The white-hot emotions which informed much of the contributions may seem, at this remove,

somewhat over-stated and comical, but they provide a fascinating insight into what was, in

essence, a cultural civil war with dance as the arena of combat. |

.......

|

When people would be going to

America for the first time, there was nearly always a dance held in their parents house

and their own people and friends and neighbours would be there.......... It was a

lonesorne sort of dance because the son or daughter of the house was leaving to go so far

away ..............And in many cases they were leaving, never to return, although they

didn't think that at the time. You might say it was a dance with a gloom over it. The

members of the family that were remaining at home would be the saddest of them

all.........There was always a cloud hanging over a dance like that.

Weddings in general were celebrated with much dancing both in the future bride and groom's

family homes and after the wedding in the couple's new home. A particular feature of some

wedding dances was the abrupt arrival of strawboys, dressed in suits and masks of straw,

who used their disguise as a licence to engage in all sorts of "jig-acting". It

is said that occasionally a disappointed suitor of the bride would vent his spleen under

cover of his straw mask. Such an intruder would often roughly claim a dance with the

bride, even when she was unwilling. Tricks with sexual innuendo were often played, and

since custom forbade the hosts to refuse hospitality to the intruders, an uncomfortable

situation could arise until the strawboys finally melted away into the night.

These dance occasions which are now but a memory are looked back on with great fondness by

all those who participated in them. The death of the country house dances is bitterly felt

and their epitaph could well be written in the words of the late Junior Crehan of Mullagh,

west Clare: "The country house was our school where we learned to play music and

dance and it was a crying shame it was closed against the country people." Voices

from all over the country would undoubtedly echo Junior's heartfelt statement. A way of

life is now no more. Its demise was not gradual and natural. On the contrary, it was

brutally and prematurely ended. All the more reason to lament its passing. |

Another form of social pressure applied by

some priests was the threat to refuse a reference to a parishioner who attended a dance

proscribed by them.

Musicians who played for the dance were also a target. In Kerry, I was told of an

instance when a local priest refused absolution to a musician he saw playing at a dance in

the 1930s to put pressure on him to stop. So deep was the hurt and alienation felt by

some musicians at their treatment that many of them left Ireland for good. Captain Francis

O'Neill, the noted collector of Irish dance music, and himself a traditional musician, met

many such men in America. Writing to Fr Seamus O'Floinn of Cork in 1916, he says:

"Not few are the pipers and fiddlers thus forced into exile by the unwarrantable

harshness of the clergy who never outgrew the bitterness arising from their experience and

to such a degree had the sense of wrong rankled in their breasts that some now in Chicago

and in the enjoyment of prosperity decline to figure on the programmes of church

entertainments."

Such was the fear engendered by the priest's perceived power that his authority was

rarely challenged. occasionally, however, he might meet outright opposition. A story is

still told in west Clare about the travelling dancing master Pat Barron, who persisted in

teaching dancing and holding dances in a disused house despite the priest's disapproval.

One day the priest threatened him. "If you don't cease to promote dancing in my

parish against my express wishes, I will have no alternative but to turn you into a

goat." Quick as a flash Barron replied, "if you do, Father, the first thing I'll

do will be to puck you in the arse."

Because the dancing masters were often the focus of dance activity in an area, they

bore the brunt of clerical disapproval. Johnny Leary "kept dance schools" in the

Kilrush district of County Cork in "any old vacant house that he could get ... It was

often very hard on him because the priests often objected to his dance schools."

In the 1920s the Church leaders' opposition to dancing focused on condemnation of

privately run dance halls. The Catholic archbishops and bishops of Ireland issued a

statement on the "evils of dancing" on 6 October 1925, which was to be read at

masses during the Ecclesiastical Year. They advocated the strict supervision of dancing

and warned of the "occasions of sin" involved in night dances: "Given a few

frivolous young people in a locality and a few careless parents and the agents of the

wicked one will come and do the rest."

An Irish Times editorial of 2 March 1929 echoed the bishops' statement:

"The clergy, the judges and the police are in agreement concerning the baleful

affects of drink and low dancing upon rural morals. Further restrictions on the sale of

drinks, a remorseless war on the poteen industry, the strict supervision of dance halls

and the banning (by law if need be) of all night dances would abolish many inducements to

sexual vice."

Another target of the moralists was "imported dances of an evil kind", or

so-called "dubious dances". The bishops' pastoral of 1925 urged the populace to

confine themselves to "Irish" dances, which have as one of their chief merits

that "they cannot be danced for long hours ... They may not be the fashion in London

or Paris. They should be the fashion in Ireland." Giving their apostolic seal of

approval they conclude: "Irish dances do not make degenerates."

On 19 October, a letter in the same newspaper from "Exile on the Continent"

declares that the "dance craze rampant in Clare and Ireland is both scandalous and

mystifying ... Even in Paris or Monte Carlo where there are dens of vice dances would

never continue to 5 am."

The first prosecution in Clare under the Dance Hall Act was in November 1935. The case

was reported under the heading:

KILKEE COURT

TALE OF THE FLUTE PLAYERS

'A BOB A HEAD'

KEEPING OUT THE COUNTRY BOYS.

M.M. of Kilkee was summoned for holding a dance contrary to the Dance Hall regulations.

Sergeant Carroll stated that on the 1st of August he was on duty in Kilkee in civilian

attire and was accompanied by Guard Kiernan. When passing the defendant's house he heard

music and noise as if a dance were in progress. He went to the door and it was opened by a

man called M.M. who greeted the witness with words, "Pay up: bob a head".

Witness paid 1/- and went in and found five boys and five girls sitting around the

kitchen. There were two flute players present. Mrs M. was also present. When approached

she claimed the dance was free and "that she had told the man on the door that if any

'country boys' came to say that the charge was 1/- per head, just to keep them out."

The judge imposed a fine of £3 reduced to £2 on the appeal of Sergeant Carroll who

said that the defendant was a very poor man.

As stated elsewhere, it was not uncommon for poorer families to run dances in their

homes for which admission was charged in an attempt to supplement their income. The

conviction in the Kilkee case showed that the new legislation made this practice illegal.

However, the reports of prosecutions under the Dance Hall Act show that even private

functions such as a dance given by a farmer for the workers who had helped him save his

crops were to be subject to licence. It can be seen from these reports that even the judge

appears to be somewhat mystified by some of the ramifications of the new act.

M.W. of Shanaway West was summoned for having a dance in his house without first having

obtained a licence.

Sergeant Murphy said that he had not been at the dance himself but after the dance he

went to the defendant's house and having cautioned him he made a statement admitting that

he had held a dance at which 26 girls and 40 boys attended. There was no charge for

admission and tea was supplied at the defendant's expense. He got up the dance for his

neighbours who had helped him to save the crops.

The case was dismissed.

D.D. of Dunsallagh was also summoned for holding a similar dance without a licence.

Sergeant Murphy said he took a statement from the defendant who admitted giving a dance

to the boys and girls who had helped him with the turf and potatoes. The Justice asked the

Superintendent why the case had been brought at all when there was no question of payment.

The Superintendent said that if dances were allowed in houses of this sort without licence

everyone could attend for miles around and the Act would be defeated altogether. If he

heard there was a dance in a country house there was nothing to prevent him going if these

things were allowed to go on. The defendant said he was ignorant of the law on the matter

or he would not have allowed the dance. He gave an undertaking to the court that he would

not offend in that respect again.

The justice found the charge proved and, dismissing it, said that "this type of

dance was absolutely illegal and in future there would be severe penalties for getting up

a dance such as the dance in the present case and in the previous case too, probably. It

would be the last of those cases that would be dismissed under the circumstances."

A further instance in which the 1935 act made inroads into long-established social

custom and practice was a prosecution for holding a "gamble" - a night of

card-playing with prizes for the winners, which was particularly popular coming up to

Christmas. It seemed that even such domestic festivity was not immune from prosecution.

In Ennis District Court on 10 January 1936, M.K. of Clonbooly was summoned for having a

dance in his house, "A gamble for turkeys was also held in the defendant's house on

the 11th December." The guests paid 1/- each for the gamble. When the gamble was

over, they took part in a dance which finished about 4am. About thirty people attended and

there were three turkeys. The man of the house provided tea with bread, butter and jam.

The defendant said that his daughter had asked for a few "sets" and he agreed.

Superintendent Keenan said similar things were happening all over the locality. The

justice said it was happening in every locality in the county. The defendant was found

guilty and the Probation Act applied.

The 1 February 1936 edition of the Clare Champion contains a report from Sixmilebridge

Court which provides an unusual insight into the tensions which were beginning to surface

around the operation of the Dance Hall Act. In open court, the justice makes the following

remarks:

"It was a very invidious thing for the Parish Priest to write to me and say that

if I granted any more licences I would hear more about it. I hope I will get no more

letters of that description from that quarter or from any other quarter either."

Such a public rebuke must have caused raised eyebrows in court, at the very least.

The year 1936 saw a continuation of prosecutions under the Act. The long-established

practice of running informal house dances was not easily relinquished and the interference

of the state in domestic merrymaking continued to be challenged. A widow living in

Cooraclare was summoned in February after the sergeant was passing her house at 1.30am and

saw a lot of bicycles and heard music. In the kitchen there were about thirty persons.

Some present had come from long distances, as far as Kilmihil, some twelve miles. A set

was in progress, dancing to the music of a flute played by a young chap who was sitting in

the corner. There was no one at the door and no charge. The defendant held dances

regularly in her house, before and after the act. She did not charge as she had no need of

money. She ran dances for neighbours who helped her with her farm. The judge expressed

surprise that:

"... this lady, whose dancing days in the natural order of things should be over,

had organised a dance and invited people there. She was not very flush in the world's

goods; still she could bring people there and have a dance in her house. He could not see

what amusement she got from watching people dance up to 2 am when she should be in her

bed."

The judge's bewilderment was addressed by the solicitor for the defence, Mr T.F.Twomey,

who told the judge that "it was a general thing in the country to set a house or two

aside for this sort of thing and the defendant's house was suitable and was one of these

houses. As a rule people did not frequent houses where there were young children."

The judge is still unclear as to why the defendant - an elderly woman - should wish to

be out of her bed at such a late hour watching dancers, and demands an explanation. Her

solicitor continues that "she did dance in her day herself and on this occasion it

was Christmas time and it was nothing unusual to have a dance up to that hour. On the

occasion of the Sergeant's visit, the dance in progress was the last dance of the

night."

Various witnesses who were present on the night were called and a spirited defence of

the night's fun was mounted. It was stated that "all the people who attended were

present on the invitation of some member of the family", contrary to the evidence of

the sergeant who had maintained that it was an "open" dance. The judge, in his

summing-up, said that the legislature never intended that a person could not invite a few

neighbours to his house for the purpose of having a dance. He dismissed the prosecution.

This judgement was important in that it finally recognised the nature of many informal

nights of social dance which had been severely curtailed by less liberal interpretations

of the act. Notably, the defendant in the case was at pains to state that she was not

running the dance for economic reasons. This was one of the factors which swayed the

judge's decision to acquit her.

Contrary to the perceived notion of County Clare in this period as being entirely

composed of cosy homesteads and well-stocked barns, the reality was that unemployment and

poverty were rife in both rural and urban areas. Initiatives by the local authorities to

alleviate appalling overcrowding in towns such as Kilrush and Ennis, described as

"slum clearances" by the contemporary local press, were constantly in the news.

An issue of the Clare Champion of 1936 refers to a demonstration of the unemployed led by

bands in Ennis to demand relief and records heated scenes at the December meeting of Clare

County Council when 300 unemployed men pleaded for Christmas dinner for their families. In

this context, it is not surprising that when Mr P.C. of Considine Terrace, Ennis, applied

for a licence in September 1936 to hold a dance in his house because "he was out of

work and wanted to pay his rent", the judge granted him an 8pm to 12arn licence

because of his situation.

However, in some quarters, the economic climate was secondary to the perceived danger

to the moral health of the nation. Opposing a proposal to hold a regatta dance in

Courtrnacsherry, the local parish priest declares:

"Revolution and the overthrow of law and order do not happen overnight but are the

result of long sapping and mining the foundations of Christian behaviour immorality and

impiety are the twin dangers which Christianity must overcome in the new world which is

now in the making. Is it not a moment for us in Ireland to weaken any of our defences, to

make light of the immodest dance, the startlingly nudist costumes that confront one in

every street, the still more flagrant nudist bathing costumes on every seashore."

The controversy surrounding the morality of dancing continued into the 1940s and is

reflected in views such as the following, published by the Gaelic Athletic Association.

Condemning many foreign dances as "negroid imitations", the writer, who may have

been expressing a personal view, recommends the promotion of Irish dances in that 'It is a

fundamental characteristic of Irish dancing that the nearest approach to contiguity is the

joining of outstretched hands. They should secure universal and parental approval."

The dances referred to in this context are the group dances fostered by the Gaelic League

which were confined to organised ceilithe.The popular dances of the period were the sets,

which were dismissed by the Gaelic League as "foreign dances".

In a typically irreverent account of the dance customs deriving from the notion of

dance as an ideological battleground, the writer Flann O'Brien proclaims:

"Irish dancing is a thing apart. There is perhaps one "ceilidhe" held

for every twenty dances. The foxtrot and the Fairy Reel are mutually repugnant and will

not easily dwell under the same roof. Very few adherents of the "ballroom" canon

will have anything to do with a jig or a reel. Apart from the fact that the Irish dance is

ruled out in most halls by considerations of space or perspiration, there is a real

psychological obstacle. It is a very far cry from the multiple adhesion of enchanted

country stomachs in a twilight of coloured bulbs to the impersonal free-for-all of a

clattering reel. Irish dancing is emotionally cold, unromantic and always

well-lighted."

O'Brien, moreover, was well aware of the to-ing and fro-ing involved in the

administration of the 1935 Dance Hall Act:

" Some district justices have a habit of taking leave of their senses at the

annual licensing sessions. They want Irish dancing and plenty of it, even at the most

monster "gala dance." They believe that Satan with all his guile is baffled by a

four-hand reel and cannot make head or tail of the Rakes of Mallow. I do not think that

there is any real ground for regarding Irish dance as a sovereign spiritual and

nationalistic prophylactic."

The iconoclastic views of Flann O'Brien were probably not very well received in

official circles at the time, but they could, in retrospect, be seen as providing an

antidote to the painful political process which underlay the turbulent years of the 1930s.

...........

As we have seen, Irish dancing on stage had

largely come to mean a stiff-backed performance by a troupe of young dancers wearing the

regulation dance dresses rigid with embroidery. An honourable exception to this is the

Siamsa Tire show in Tralee, County Kerry, which has incorporated steps from the older

traditional dancers in the area into its repertoire.

Yet here in the 1990s, in the unlikely

setting of the Euro-extravaganza, appeared a totally new dance phenomenon produced by

RTE's Moya Doherty. It featured a veritable chorus line of attractive young women with

long flowing hair, clad in short velvety dresses and partnered by young men in fashionably

cut black trousers and flowing shirts, who provided the choreographical accompaniment to

the leading pair who danced a love duet, Irish style. The familiar batters, shuffles,

drums, rocks and cuts were all there; the dancers wore the specially engineered black

footwear which had hitherto seemed so unglamorous. But this was Irish dance as it had

never been seen before: an unashamedly spectacular display which, for once, accepted the

sexual undertones of the dance and revelled in its power. The sound was magnified to a

volcanic rumble by the combined power of the dancers' feet. The accompanying music by Bill

Whelan had Irish overtones but was obviously newly composed. Its rhythms underlay the

thunderous footwork of Flatley and the balletic movements of Jean Butler. The result was

electrifying. Ireland was agog. The familiar had been utterly transformed. Riverdance was

in spate. Its power could turn a generating station, let alone a mill. In the years since

1994, the Riverdance show has become the single most successful production using Irish

dance as its centrepiece. Acres of print have been produced, analysing and commenting on

the Riverdance phenomenon, most of them eulogising its achievements, although occasionally

a dissenting view has bubbled to the surface. Currently, the commercial success of

Riverdance continues unabated with three separate troupes under the names "Lee",

"Liffey" and "Lagan" (the names of Irish rivers) touring the world to

continued acclaim. With Michael Flatley's break from Riverdance came yet another

large-scale stage presentation using the vehicle of Irish dance. Flatley's Lord of the

Dance was created as a showcase for his particular tap-influenced style. The costumes and

settings were pure vaudeville......The former much resented image of the Irish male dancer

as a sissy in a skirt has been replaced by the iconography of black-leather sheathed

thighs and oiled pectorals.

Street Games, County Louth, undated.

One of many photographs of

historical interest in Helen Brennan's book. |

After Riverdance and Lord

of the Dance, registrations in Irish dancing schools more than doubled..... The world of

the Irish dancing schools is largely the preserve of children..... this contrasts very

much with the other main dance event of the recent past, namely the revival of set

dancing....One of the key elements in the tremendous success of the set dancing movement

was, undoubtedly, the presence of a generation who had grown up during the Irish music

renaissance of the 1960s and 70s and had experienced the music as merely passive listeners

to a performance... they could, for the first time, really participate in the world of

Irish music, even if they didn't aspire to play a note.

The initiation of classes in set dancing at the 1982 Willie Clancy Summer School in

Miltown, Malbay, County Clare, was, more than anything else, the spark that lit the

revival's fuse..... Manuals of set dances were produced and collecting trips were

organised to talk to older dancers and piece together sets which had fallen into

disuse.... the old plain set which had died out in Clare, was revived by Connie Ryan in

the 1980s.

At present (1999) there are over seventy set-dancing classes running weekly, as well as

countless workshop weekends and literally hundreds of ceilis and set sessions. There have

never been so many people dancing in Ireland, never so many experiencing the "joy of

sets". |

In the nearly twenty years since Helen

Brennan's book was published, several Irish Set dance groups and organisers have used the

'Sets / Sex' connotation including of course, Sets in the City.

Doing proper Irish 'steps' is very

difficult. Try these : steps1

and steps2 . There are dozens of

examples on youtube.

|

Thus both the old 'stepping'

type of Irish dance and the 'sets' that are nowadays so popular across the world underwent

revivals and became a part of present day Irish identity in a way and to a degree that has

not happened with English Country Dance.

The 'folk hero' status of Irish dancing masters is well illustrated by the reverence in

which people like Connie Ryan are held, even decades after their death.

This photo from Connie Ryan's funeral in May 1997 is available on the internet.Connie Ryan lived largely before the internet and

youtube age - there are therefore few recorded examples of his teaching - here is one

A tribute from the Irish Times is here.

|

The history of dance in England was

covered in a recent BBC TV series 'Dancing Cheek to Cheek' with the serious discussion

being provided largely by Dr Lucy Worsley, an academic historian.

Here are some notes from the series - if it

is repeated on television at some stage be sure to watch it!

In C17 (seventeenth century) dancing was

considered to be dangerous and debauched - yet within 150 years it became an essential

social skill.

In effect, dance moved from being

considered as 'the work of the devil' to a desired form of 'high art'. Dance had always

offered the prospect of romance - a rare chance to 'get to grips' with the opposite sex.

In C17 the 'cushion dance' was popular but

frowned upon by the clergy especially as 'raunchy and dangerous to public morals'. Some

likened it to prostitution, yet it remained a firm favourite dance in England. In 1633 the

puritan William Prynne published a 1000 page denunciation of both dance and stage plays.

Publication of his Histrio Mastrix was however seen as a veiled attack on the royal family

- so he was imprisoned in the Tower of London and his ears were cut off.

Maypole dancing was effectively banned

during the English Civil War (1642-1651, although actually a series of three shorter wars

and involving the whole of Britain and including Ireland) yet in 1651 John Playford

published his book of dances - The English Dancing Master. It was a brave thing to do at

the time but his intended market was the Gentlemen of the Inns of Court and the landed

families who took up dancing (and fencing) as social skills.

Interestingly, the start of the 'English

Civil War' can be traced to a rebellion in Scotland in 1637 and centred upon the attempted

imposition of a particular version of religion - no surprise there then! The period 1651

to 1660 was characterised by political uncertainty and infighting and includes Oliver

Cromwell's period as 'Lord Protector' until his death in 1658. In 1660 the monarchy was

finally restored under Charles II - and a 40 foot high maypole was erected in central

London, giving the royal seal of approval to what had previously been a questionable

pastime. These decades were also the time of the Levellers and the Diggers.

Playford's dances were taken to France and

from there spread throughout Europe - and further afield. The influence of the court of

Louis XIV was strong - and this became a golden age of dancing, one in which the Minuet

Dance became the height of fashion and achievement. It offered similar chances of

flirtation as did the cushion dance - there was lots of eye contact and some touching -

but it required learning some fancy footwork. It was a sort of equivalent to Scottish

County Dancing - difficult to do properly yet performed in front of a crowd.

It was an age of rigid social customs - yet

dance offered a chance to push the boundaries. Dr Ricardo Barros of the Royal Academy of

Music, interviewed by Lucy Worsley put it thus:

"It was required by Louis

XIV to convey emotions though dance. People were so crushed by rules of etiquette, how to

hold an arm, how to bow deeply, with dance they could let their hair down, not only COULD

you express yourself a bit, you were expected to. Dancing is nothing if you just consider

steps, you have to express yourself with the eyes, face, gestures and convey your passions

to the others".

This was a far cry from the views of the

clergy both in England and Ireland - as indeed it is today from the views of the boorish

self-appointed arbiters of folk dance etiquette in the UK.

Dr Barros is also on the staff of

musicdevon.com - who offer "music lessons with inspiring teachers in Devon". (I

live in Devon yet I'd never heard of them before!)

For two centuries, dancing masters became

central to English Society. Many of them were both French and despised. Some had a sleazy

reputation, but anyone who was anyone had to dance the minuet - and that required proper

teaching.

In 1732 the grand Assembly Rooms opened in

York - these were the most magnificent in England and Britain's first purpose built dance

hall. Amazingly it was built using what might these days be called 'crowd funding' - but

ability to pay was the key to admission despite it's egalitarian leanings. For the

'refined and correct' Georgian era it became an elegant 'meat market' with plenty of

liaisons outside of dance - and well as much wheeling and dealing for business people,

maybe much as jive dance is today for liaisons and golf is for wheeling and dealing?! Yet

this was still an age of 'correct behaviour' and guide books were available on 'genteel

behaviours' - all of which has now died out.

Yet people tired of the difficulty and

formality of the minuet - they wanted something that was more fun and physical. In any

case men had started to desert the dance halls and in the Victorian Age - characterised by

so many rapid innovations and changes - dance became "fast, frantic and giddy".

Thus in the C17 society split between those

who danced and those who didn't (or who deeply disapproved of the whole process). By the

C18 dancing had largely lost its dubious reputation - but new dances were set once again

to be condemned. The polka - with its rustic peasant origins became a new craze for the

upper classes. The waltz, originally developed in C18 in Europe shared one feature with

the polka - that of holding ones partner scandalously close - something you could not do

in the minuet!

Following on from the opening of 'Assembly

Rooms' dance clubs were opened in London and elsewhere - one of the most famous being

Almacks in St James. It offered little by way of food or dance but was 'the place to go'

to meet people - maybe an early form of speed-dating? It was the 'hottest night-spot' in

Regency London yet when the numbers of men dwindled the owners (a group of ferocious

women) introduced quadrille dances to lure them back. When that didn't work they

introduced the new 'dirty dance' that had been sweeping Europe - the waltz! It became an

all-consuming passion for some members of high society, including Lady Caroline Lamb.

Scandals surrounding the waltz and what it

would do to public morals boiled over in the Times newspaper in 1816 - where it was

denounced as a 'fatal contagion'. But by 1844 the polka was first performed on stage and

by 1850 was (together with the waltz) hugely popular. Attention then moved for a while to

Scottish dance - the eightsome reel and similar - yet by the end of C19 men had retreated

from dance, even from the polka. In England an 'anti-dance' attitude amongst men has to

some extent been maintained to the present day - in sharp contrast to the popularity of

Irish dance in Ireland - and elsewhere in the world.

Yet by the turn of C20, Victorian ideas and

dances such as the waltz were considered a bore. New forms of dance were desired and were

imported from the Americas - ragtime (1890 to 1910), Charleston (1920s), Argentinian tango

(1912 -). The latter especially had sexual overtones that (once again) were too much for

the church and for some people in 'polite society'. Here was a dance in which men and

women were holding each other as never before on the dance floor - and it had to be

stopped! Even the Pope got involved - denouncing the tango as the new paganism. But people

couldn't care less what the Pope thought - they all (or most of them) danced the tango.

1915 saw some of the first dances to be filmed - high society continuing much as before

despite the horrors of war.

Maybe as an antidote to all the 'newness',

a charity worker, social reformer and suffragette Mary Neal - who according to one of her

descendants has been almost written out of history - started to promote song and dance

amongst the poor. Her contributions to Morris dance were mentioned by Lucy Worsley but

are discussed at length here. It is an article well worth reading. as is a website devoted to her life. This was the age of

Cecil Sharp and EFDSS but without Mary Neal much of it might not have happened.

English dancing was seen as 'rooted in the

countryside' as opposed to the 'new fangled imports'. Whilst Cecil Sharp has long been

accorded god-like status for his work in folk song and dance, Mary Neal was largely

ignored - owing to a rift that developed in 1907 - but she was awarded the CBE in 1937.

The cited article explains the background - and highlights that folk song and dance, like

so many other hobbies and activities, is not immune from feud and vendetta.

After the 1914-18 war, people wanted to

dance like there was no tomorrow. The Hammersmith Palais accommodated 7000 dancers - doing

the quickstep, the two-step and the new waltzes - earlier versions having been a simple

turning dance. No longer were formal 'dance masters' needed - people just danced. By the

1920s seemingly everyone wanted to dance - hence the popularity of the Charleston. It also

allowed women to break free of any male dominance and enabled individual self expression

through dance. Yet teachers wanted to reassert their authority and organise 'standardised

dances' - a parallel development perhaps to what happened in Ireland in 1935 with the

Dance Hall Act. This 'standardisation' reduced the appeal of dancing, so by the late 1930s

ballroom was considered boring (and too complicated). So another new generation of 'silly

dances' were introduced - including the Lambeth Walk.

Today, Irish Set Dance continues to have a

strong link to tradition, despite new dances being created. There is a strong appeal for

the older dances, and for doing the older 'correct' steps. In England, Morris dance is

viewed as a somewhat 'odd' pastime and in many areas dance clubs centred on 'English

Country dance' have all but died out. Ceilidh dance remains popular in a few cities -

sometimes aligned to a strong university folk dance club, yet it is often necessary to

travel a long distance to find a good 'ceilidh' on a Saturday night. There are dozens of

small 'folk festivals' throughout England - yet of these only a handful offer any good

quality participatory English dance. Notable are Chippenham (often regarded as the best

but it needs larger venues), Sidmouth, Eastbourne, Lichfield, Broadstairs, Towersey and

Whitby. At others, even if there are dances or ceilidhs the quality can be poor. Some of

these festivals are reviewed here.

Morris dancing is more widespread - but

that is only to be watched. Part of the problem is that it is more expensive to provide

good quality dance venues than it is to provide venues for concert attendees - and there

are so few accomplished dancers left anyway. You meet many of the same people at major

dance festivals. There is also some open hostility to Morris dancing and other street

displays. I'm not sure I believed it but I was told recently that during Wadebridge Folk

Festival some town shops have been known to display notices 'No Morris Dancers'. Other

people complained there were too few dance displays in the town. In Sidmouth there have

always been strong 'pro' and 'anti' folk festival arguments.

Time to bring back fun and

flirting?

The potted history of dance as given above

has a recurrent theme - the denunciation of aspects or styles of dance not only by

factions within the dance movement but also by outsiders (often the church or people of a

church or similarly self-important disposition). Within some English dance clubs

there is also now a tendency (resulting perhaps from the age of many participants) to

denounce any aspect of 'fun and flirting' and this is arguably one factor in their

decline.

Yet other types of clubs are also in

decline - the overriding factor may be that so much 'social interaction' is nowadays

conducted online instead of in person. You can now play bridge online, you can chat online

and you can play chess online - and of course you can flirt on-line via scores of 'dating'

websites. The on-line 'pornography' industry is also vast - and much of it is free to

view, paid for by advertising. It is also all too easy, on a dismal winter's evening, to

stream a Google Streetview image of Switzerland, Romania or the Scottish Highlands from an

iPad to a wide screen TV - so you can go on a tour of a scenic location without leaving

the comfort of your armchair. Or you can select from hundreds of intellectually

challenging TED.com talks. There are nowadays so

many reasons simply to stay at home. In future, risk of

infection may be an additional reason.

In past years (and centuries) moralists and religious zealots sought at every

opportunity to curtail dance or aspects of dance. Today, the church has little or no

influence in England. As a social force it has been replaced by 'political correctness',

'militant feminism' and similar movements that seek to exercise control. These find

expression in seeking to curtail fun and flirting. Feminism is discussed here - and by a woman.

Modern dance crazes include 'zumba' - where

you never touch anyone - and this is apparently hugely popular amongst young women. It may

hark back to the 'freedom' women found in the 1920's in the Charleston - they didn't need

men any more. Nowadays, instead of 'being seen at a dance' all sexual contacts can be

satisfied via dating 'apps' on smartphones. In respect therefore of what used to be one of

the principal purposes of dance - meeting people of the opposite sex (or these days of the

same sex?) - it has simply become redundant.

This point was made some years ago in my study of internet dating sites. I argued in sts80 that were a tiny fraction of the money and effort devoted to

internet dating to be diverted into folk dancing, and if meeting other unattached people

could become once again a central feature of folk dance (and other types of dance that are

also in decline in the UK such as American Square), then the prospects for a revival might

be much brighter. See also a discussion of music and dance to counter the 'epidemic' of

loneliness in the UK (song and dance to

combat loneliness).

The effects of loneliness on old people was starkly illustrated in a 'money' programme

on BBC Radio 4 in late January 2017. The discussion was on how to protect old vulnerable

people from various financial scams. One type of lucrative scam is to send people letters

saying they have won a prize, but they need to send £10 or £20 as a registration fee in

order to claim it. Relatives of one elderly person had tried to stop him or her responding

but the victim felt it was worthwhile losing money at regular intervals because they

enjoyed receiving the letters - because it made them feel as if someone in the world was

taking notice of them. Other lonely people send themselves a Christmas card (or two) just

so that they don't feel so left out. There are many examples where (usually) women have

been conned out of large sums of money via fake dating website profiles. In some cases

losses have exceeded £200,000.

Gender Neutral dancing - a

manifestation of political correctness?

Other very recent developments in the UK

(and elsewhere) include 'gender neutral' folk dancing. Here, traditional folk or contra or

ballroom dances are danced as before but without any differentiation between men and

women. For some dances it makes little difference - they can just as easily be done with

any mix of the sexes. A related development is the introduction of LBGTQ (Lesbian,

bisexual, gay, transvestite, queer) ceilidhs to the UK where the emphasis is on attracting

people who lead 'alternative' sexual lifestyles as opposed to the ancient custom of a man

being attracted to a woman, and vice-versa. I mentioned a few of these events to some of

my (female) dancing partners. So far their reaction has been 'No thank you!' LBGTQ events

have (unsurprisingly) been common in the USA for years (where the term Queer is freely

used).

Both of these developments seem to have limited appeal at the present time in the UK

albeit they are centre stage amongst the 'politically correct'. Bristol Contra

is apparently one example - as of 2022.

I'll outline 'gender neutral' folk dances elsewhere but basically, instead of a man's

line and a ladies line in a longways set there is an A line (used to be men) and a B line

(women). Anyone of any gender can be in any line, we are all just 'people' now!

In a square set, 'couples' are an A on the

left and a B on the right. So what used to be called as a ladies chain is now a B chain -

and the people in the B positions go into the centre of the set to take right hands - etc.

The more unusual man's chain is now an A chain - and the people in the A position go to

the centre of the set and give left hands. Except in many Irish Set dances where men's

chains are done with a right hand, just to confuse the issue. Thankfully, Irish Set dance

seems not yet to have been infected by political correctness - men dance wherever possible

as men and women have to dance sometimes as men simply because there may not be sufficient

men to go around. Quite often there are too many men, which is an appalling state of

affairs.

Additional interesting videos and

links - some of them about dancing. Recommended viewing for despots (and normal people).

If you wish to see the possible future of

gender neutral 'liquid lead' ballroom dancing, try

this TED talk.

Or for a brief history of social dance in 25 moves - (rather too energetic for most

folk dancers!) watch

this.

Here is a politically correct discussion including dance

for fat people (yes, really!)

My next recommendation for broadening the minds of people in the folk dance world is a

talk by a

truly inspirational Canadian woman. It has nothing to do with dancing or disputes

about etiquette but everything to do with how women can show they don't need preferential

treatment or mollycoddling - just equality. If only there were more like her in the world.

She's one of the most amazing people I have ever seen on TED.com and a worthy winner of

the Canadian kickass award.

Criticism of some expressions of feminism were also given Camille Paglia, a renowned

and contentious American academic. She discussed the logic of feminism in an article in

the Spectator (UK) in 2016. An excerpt and discussion of the sexual roots of dance is here.

Here is a 'financial' TED talk by a man. It shows the bravery and dedication of people

who confront real evil, as opposed to control freaks and despots who moralise about

different dance styles. It shows how

dedicated journalists helped unravel the story of the Panama Papers.

The next example (by a woman) is centred on misuse of money on a large scale and the

role of western banks in colluding with dictators (add link) . I gave some lectures on

charity funding about 20 years ago that included the same ideas. (link

to charity section)

My dance diary for 2016 - and highlights

Folk dance section (local club venues and dances)

Some of my letters and articles on folk dance published in Set and

Turn Single, 2011 to 2016.

home page